For decades, Tom Mercaldo, president of Aquinas Consulting in Milford, Connecticut, relied on a combination of full-time employees and independent contractors around the U.S. to serve client needs, scrupulously following longstanding guidelines from the IRS to avoid trouble—and keep everyone happy.

For decades, Tom Mercaldo, president of Aquinas Consulting in Milford, Connecticut, relied on a combination of full-time employees and independent contractors around the U.S. to serve client needs, scrupulously following longstanding guidelines from the IRS to avoid trouble—and keep everyone happy.

Then came California Assembly Bill 5. In January 2020, the state passed the new law reclassifying who counted as a contractor and who was, at least in the Golden State, now an employee. The law was passed to rein in big tech companies and regulate the emerging “gig” economy, but it swept up plenty of others, like Mercaldo. “They’re a legitimate business according to the IRS, but under the…rules in California, they’re not a legitimate business anymore,” Mercaldo says of his contractors. “The law is so broad. It is being applied in many areas that don’t make sense at all.”

Now, Mercaldo is fighting a rear-guard battle to figure out who is what, based entirely on where. Worse, because the the company hires people across many industries, he’s concerned he could be forced to re-classify an independent contractor who works as an accountant for the consulting firm, even though a business in another industry wouldn’t have to. “The definition of whether [someone] is a contractor or an employee should not have anything to do with what my business does,” says Mercaldo. Aquinas no longer operates in California.

It may not have been part of your pre-, or even post-Covid human capital plan, but remote work seems to be here to stay. By 2025, more than 36 million Americans will be working remotely, an 87 percent increase over pre-pandemic levels, according to the 2020 Future Workforce Pulse Report by Upwork. In an ever-intensifying war for talent, companies will need to incorporate some remote work in order to attract and retain the best.

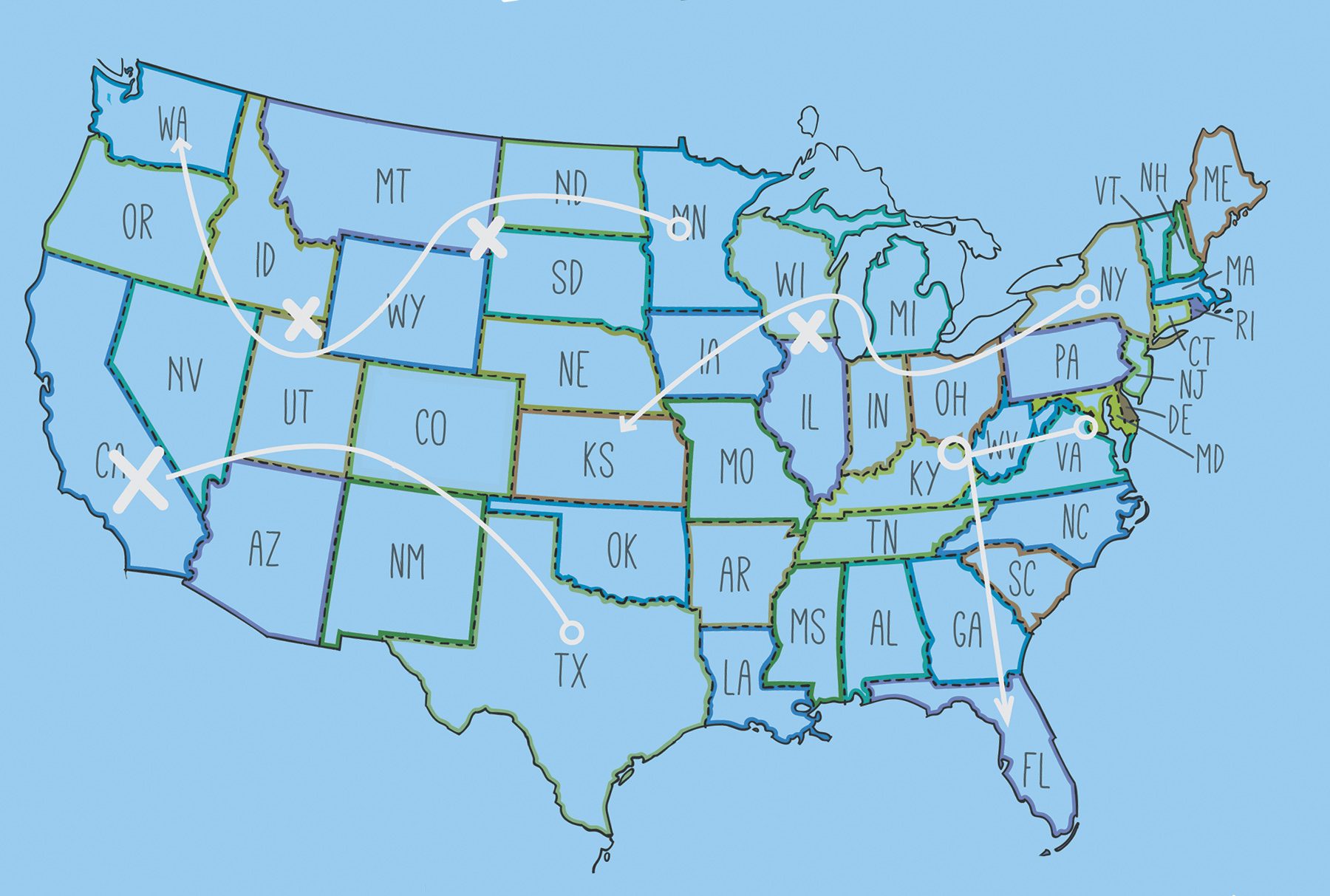

But when it comes to employment law, all states were definitely not created equal—and where your remote employee or contractor lives and works could have unforeseen and, in some cases, significant implications for your business. These likely aren’t dealbreakers, by any means. But they will add complexity. It pays for you and your CHRO to get smart now about the diverse rules around remote employment, so you can adjust your hiring strategy to reap the rewards of a wider talent pool, while minimizing the costs and administrative burden. “I don’t think anyone thinks we’re going back to the way it was,” says Michael Cardman, a legal editor at Reed Elsevier who specializes in employment law. Here are some places to start:

Many Questions for HR

Because employment laws apply in the state where the employee is actually doing the work, having even one remote worker could create a “physical nexus,” akin to setting up a satellite office, depending on the state. Colorado and Virginia are examples of states that treat telecommuters as constituting a tax nexus, and have not waived those statutes during the pandemic.

Regardless of where your company is based, you typically will need to withhold in the states in which remote work is being done and pay into unemployment in those states as well. That means if you hire a remote employee in one of the nine states that have no income tax—Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Washington and Wyoming—no payroll tax on that worker will be due, even if your company is based in a high-tax state, such as California, New Jersey, Oregon or Minnesota.

Your HR department should also be familiar with any reciprocal tax agreements your state has with other states. Illinois and Wisconsin, for example, have a reciprocal tax agreement stating that if an Illinois employer hires an employee who lives in Wisconsin, that business can withhold income tax from the employee’s state of residency. Therefore, if your company were based in Illinois and you hired Wisconsin employees to work remotely, payroll taxes will be deposited with the state of Wisconsin.

Changing rules around salary disclosure could also add administrative challenges for HR. For example, a new Colorado state law requires companies advertising a job to disclose the expected salary or pay range for that position, including for remote work positions. To avoid having to add pay ranges to job descriptions, some employers instead began adding language that excludes applicants from Colorado from applying. Johnson & Johnson recently posted an ad recruiting a senior manager, noting that, “Work location is flexible if approved by the Company except that position may not be performed remotely from Colorado.” HR managers will need to keep up with similar changes made by other states going forward.

Here Comes SCOTUS

It’s worth noting that the rules governing nexus may change based on the outcome of a lawsuit that could go before the U.S. Supreme Court later this year. In 2020, when residents of New Hampshire who previously worked in offices in Boston started working from home into during Covid, they should have stopped incurring income tax because New Hampshire doesn’t have one. But Massachusetts issued guidance temporarily superseding its existing laws, such that income earned by nonresidents working in Massachusetts before the emergency declaration would be taxable as Massachusetts-source income.

New Hampshire sued, claiming the move was an unconstitutional tax grab. If SCOTUS agrees to hear the case and decides for the plaintiff, things may get easier for employers of remote workers. But Randle Pollard, attorney in Ogletree Deakins’s Employee Benefits and Executive Compensation group, says that we should expect to see more state maneuvering as they realize they will be losing tax income. “They’re saying, ‘Uh oh, we’ve got to protect our tax space.’”

‘Convenience of the Employer’

One way they can do that is to strictly enforce rules that extend the reach of a state’s taxing jurisdiction beyond its borders. Seven states—New York, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Arkansas, Nebraska, Delaware and Alaska—have “convenience of the employer” rules stating that out-of-state employees can only be considered remote for tax purposes if the employer can prove it’s due not to employee choice, but the employer’s necessity, such as insufficient office space. But that’s not always simple, says Pollard. “Even during Covid, New York has never found that a governmental order to stay at home constitutes the necessity of the employer—which is incredible. You would think that would meet the requirement because you have to shut down and your employees can’t come to work—but no.”

Meanwhile, some cities and states are becoming even more proactive about bringing in remote workers, offering significant incentives for relocation. Ascend West Virginia is a campaign by the state to lure remote workers with promises of $10,000 or more and free coworking space. Maine is offering tax rebates totaling up to more than $15,000 to transplants with college degrees. Alaska is paying new arrivals $1,000 per year for three years. Individual cities, such as Baltimore, Maryland, Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Topeka, Kansas, are floating subsidies such as cash lump sums, home loan down payments and even mountain bikes to lure new out-of-state workers. If these campaigns are successful, employers could find they have newly transplanted workers suddenly in states with a host of different rules.

In addition to payroll tax, companies need to understand all local employment regulation related to wage and hour rules, termination of employment, noncompetition and sick and family leave rules. For example, California, Florida, Michigan and New Mexico are just a few of the 30-plus states with a higher minimum wage than federal. Different states also have differing interpretations of wrongful termination, breach of contract and discrimination, among others. Family leave regulation also can vary widely, says Amber Clayton, director of the knowledge center at Society for Human Resource Management.

“Someone in California might be eligible for the pregnancy discrimination leave and somebody in another state might not be eligible for anything other than the federal family medical leave,” she says, adding that companies with more general policies may need to publish new employee handbooks drilling down to the state level, “especially those companies that may not have been multi-state employers previously.”

The Contractor Conundrum

Companies won’t necessarily be able to avoid the administrative and financial complexities associated with remote employees by trying to increase the percentage of contract workers. The line between employees and contractors has been become more complex since the start of the pandemic and is poised to only grow more challenging as more of the workforce goes remote, says Patrick Anderson, CEO of Anderson Economic Group. “[Flexible and remote work] now encompasses a substantial portion of our workforce, including many people who always thought of themselves as owners of their own business, as well as people who thought of themselves as employees,” says Anderson.

Legislators have sought to address worker classification in recent years. AB5, the California law that swept up Mercaldo, uses the “ABC” test. To remain a contractor, it says: (A) the worker is free from control of the hiring entity, (B) the worker performs work outside of the usual course of the entity’s business, and (C) the worker is engaged in an independently established occupation or business of the same nature as the work performed.

At the federal level, the Protecting the Right to Organize Act of 2021 passed the House in early March and now sits with the Senate. One of its most contentious parts amends Section 2(3) of the National Labor Relations Act to redefine employee status using the ABC test. In an effort to prevent misclassification, the Biden administration has indicated it would like all labor, employment and tax laws based on the ABC test.

While these laws targeted companies like Uber, opponents of the ABC test say the “B” prong will eliminate independent contracting in many industries and harm small businesses and workers. Until AB5 passed in California, the definition of a contractor was “pretty clear,” says Mercaldo. Typically, contractors have a separate business identity (and are often incorporated), a federal tax ID number, business registration, a web presence, multiple clients and perform services outside of the employer’s control.

Crushing Small Businesses

If the PRO Act were to pass with the ABC test in place, some companies would be forced to make their contractors employees. Just as likely, says Mercaldo, many employers will consolidate those roles, hire less or outsource positions overseas. “When you have policies that make it more economical or reduce an employer’s risk to work in a location other than the U.S., you will see more of that,” says Mercaldo.

A bigger issue is that it would limit small businesses that rely on contractors to reduce overhead and have the ability to scale up when they’d never be able to bring on employees. Small businesses use independent contractors to perform critical tasks in their line of work, says Eric Groves, CEO of Alignable. An Alignable survey found nearly half of small companies who hire contractors said 25 percent of the time they are doing work performed by in-house employees.

Rantoul, Illinois-based Taylor Studios designs exhibits and installations for museums, visitor centers and corporate facilities. The company has been in business for nearly 30 years and has worked on more than 700 projects around the country. Taylor occasionally uses freelancers because the work is project-based, often in different locations and has peaks and valleys, says Betsy Brennan, owner and president of Taylor Studios.

However, because these contractors work in the field of design and Taylor Studios is in the design business, it would likely fail the ABC test as proposed in the PRO Act. Brennan is hoping such legislation won’t pass, but she’s not yet sure what she will do in the event it does. It is unlikely that Brennan would be able to bring on many contractors as employees. “You’d just bring them on, lay them off, bring them on, lay them off. It wouldn’t make sense. And many don’t want to be employees,” she says.

Groves forecasts a further rise in flexible work models due to younger generations placing a higher value on work-life balance. Many independent workers now report not only greater flexibility but better pay and more security than through traditional jobs. Among full-time independents, the portion saying they wouldn’t go back to a conventional job rose from 53 percent in 2019 to 61 percent in 2020, according to a report by MBO Partners. “They’re going to want more flexibility. They’re going to want to be creative with their careers in new ways that are good for the economy,” says Groves. “I hope that people in Washington don’t do things to make us less competitive.”